Culture Shapes Inclusion Before Leaders Act

- cfizet

- Dec 8, 2025

- 3 min read

Updated: Jan 9

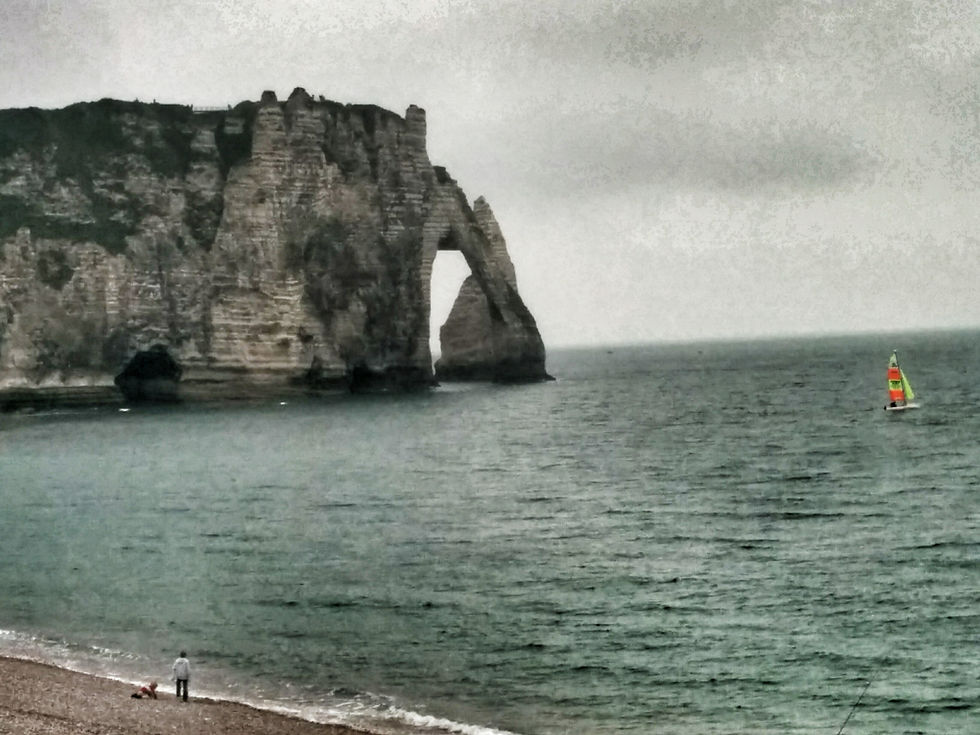

La Roche Percée, Normandy, France

As promised, here’s Article #1 in my 4-Part Series on Inclusion Across Cultures — setting the stage for what’s ahead. Alright, let’s dive right in!

Why Culture Matters First

Culture sits at the heart of everything we do, long before we even start talking about the actions leaders can take to be more inclusive. Many of the structures organizations rely on every day — performance metrics, participation criteria, feedback models — may look “neutral,” but they’re deeply shaped by the cultural assumptions of the people who designed them. And unless we question these systems, even the most well-intentioned inclusion efforts will struggle to reach everyone.

Lessons from My Master’s Cohort

During my Master’s degree, I was part of a cohort of 19 students from 15 countries, studying across three European universities. At the end of our first semester in Amsterdam, we discovered that participation counted toward our grade in one of our foundational courses. Unsurprisingly, the three Canadians and one Dutch student received full marks — we had grown up in environments where speaking up, debating, and engaging professors directly was expected.

But many classmates came from cultures where publicly questioning authority or volunteering opinions in a group setting was uncommon. Their participation grades suffered — not because they lacked insight, but because the framework assumed that one very particular style of engagement was the “right” one.

A Recent Professional Reminder

A recent online course I participated in — this time with professionals from around the world — reminded me of this all over again. We were asked to use the “WWW–EBI” feedback model (What Went Well / Even Better If). At first, I thought this was universally accessible. But it quickly became clear that cultural backgrounds shaped how people used it. Some participants rarely offered EBIs — not because they lacked ideas, but because giving direct improvement-focused feedback to a peer felt uncomfortable or inappropriate in their context.

Only when I was paired with the German participant did I receive direct, detailed, completely unfiltered feedback (and I loved it — my mother is German, so this style feels like home). But it highlighted something important: even a simple feedback structure can act as a cultural mirror, reflecting what feels natural in one culture and uncomfortable or inaccessible in another.

Fix the foundation before adding floors

These experiences underscore a critical point: inclusion isn’t only about creating new opportunities or frameworks — it’s about examining the ones you already have through a cultural lens. Systems that feel fair, objective, or “common sense” to some can inadvertently exclude others.

And it’s not lost on me that, as someone from a Western, English-speaking background, the “common sense” and “objective” norms I’m accustomed to have often been the ones transposed onto educational and workplace environments — shaping power dynamics in ways we can’t afford to ignore.

So leaders who are serious about building inclusive environments must ask:

Are our existing performance measures, feedback systems, and engagement norms truly accessible, meaningful, and equitable across cultural contexts?

Rethinking Participation and Feedback

Rethinking them doesn’t mean abandoning expectations, it means expanding what counts as meeting them. Participation should be expected from all students, but it can take many forms. Speaking up is one, but so is active listening (wild idea: what if we valued listening as much as speaking?), contributing written reflections, or engaging in small-group settings. If students have spent their academic lives in systems where public debate wasn’t encouraged, holding them to a Western-centric participation standard is inequitable. Providing support and training for students to practice less familiar forms of participation not only supports cultural diversity — it also allows more introverted students to engage meaningfully without being penalized for how they naturally show up.

As it relates to feedback, rather than launching straight into WWW/EBI mechanics, start by grounding learners in why this model exists. Discuss how different cultures approach feedback, how this structure might diverge from what participants are used to, and why feeling awkward or uncertain isn’t a sign of incompetence — it’s a sign that they’re stretching into a new skill set.

Key Takeaway

Before rushing to design new inclusion initiatives, start by examining the practices, frameworks, and systems you already have in place. You’ll likely find some revealing starting points. Without cultural awareness — and without the cultural intelligence to recognize how “neutral” systems often privilege certain norms — even well-intentioned inclusion efforts can land as performative, because they’re built on foundations that unintentionally exclude.

What’s Coming

Next week, I’ll dive into real examples of well-intentioned inclusive leadership practices that worked in some contexts but fell flat in others — further illustrating why inclusion must always be viewed through a cultural lens.

À bientôt!

(This article was originally published on my LinkedIn on December 8, 2025)

Comments